Henry Moore's 'Reclining Figure'

https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/d4c7a1cdb0a3639f5e125147be9045ef10011814/0_126_1965_1179/master/1965.jpg?w=300&q=55&auto=format&usm=12&fit=max&s=cc94827a9fb487fd50d065988fccd6b8

Conceptualising our bodies

As humans we have some very strange, and largely irrational, views about, and attitudes to, our bodies.

Generally speaking, we find it relatively easy, to look on the outside, but find it much more difficult to look on the inside, where things really matter.

People have emotional problems coming to terms with some parts of their bodies, compared with others. In fact they may be repelled by the sight or functioning of some or most of their insides! Similarly they may know more about some parts than others. Facts are important, but aesthetics and attitudes have a huge impact on sensitivities and perceptions.

The 'inside world' of cells, organs, systems and processes, determines our independent existence and conscious awareness of the environment. It is irrevocably connected to, and dependent on, the physical body in which it resides, but we take it very much for granted and many, perhaps a majority, are very ignorant of what they look like or how they work.

Car Mechanic!

https://image.shutterstock.com/z/stock-photo-professional-auto-mechanic-and-woman-in-auto-repair-shop-garage-89301178.jpg

We might draw an analogy with owning a car. We drive it and expect it to go. When it doesn't we are at a loss. We may look under the bonnet/hood without the faintest idea what is there or how it works. If the problem persists we are likely to take it to the garage, and entrust it to the experts. We admit our ignorance and follow the advice of those who know better.

The longevity and performance of the vehicle depends both on the quality of the design and its treatment. So it is with the functioning of our bodies.

This metaphor may help us get to grips with ourselves but of course it falls far short of the reality, for the body is far more intricate and sophisticated than any machine. No machine (as yet!) incorporates the higher mental autonomic functions or awareness of self, inherent in the human brain, with its advanced ability to communicate, empathise, emote, theorise and create.

The mechanism is one thing, but our attitude to our bodies is far more esoteric and complicated, affected by a range of philosophical, psychological, ethical, religious and aesthetic considerations. How we treat it or react to it, may vary considerably from one culture to another, some regarding nudity as a sign of a healthy mind, others as a heinous crime.

In the liberated, liberal west, we like to think we have thrown off all the old religious inhibitions, and can now with a clear conscience literally reveal all, even on prim- time TV shows. The body beautiful is everywhere promoted - and used to promote - yet dissatisfaction with body image has never been more prevalent, leading in a significant proportion to morbid life threatening extremes of obesity, anorexia and distressing self harm particularly amongst adolescents.

A significant proportion of debilitating and fatal disease is also caused by personal behaviour and man-induced environmental circumstance.

Body Beautiful?

Humans apply aesthetic standards to the body. Since Classical times, the human body has been regarded as the height of beauty and perfection, and who could disagree.

Greek Goddess Aphrodite

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/184788390937875613/

It has been demonstrated that success in life may be largely influenced by physical beauty. It undoubtedly serves the evolutionary purpose of attracting a mate with whom the species is perpetuated. Humans are attracted and fascinated by it, as the advertising industry is well aware. When linked to a particular skill it can ensure a hugely hero worshipping career. Did human beauty emulate the gods, or was it the other way around?

Greek bronze 500 BC

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/184788390938949482/

Yet it is worth reminding ourselves this is almost entirely external beauty based deeply ingrained criteria of youthful arrangement of facial features and a physique well proportioned and athletic, free of any form of disfigurement. However if a similar attention and care was devoted to the internal organs and systems of the body, humans might not develop the multiplicity of disorders, both mental and physical, that they do.

This different perspective when it comes to the interior of the human body is a cultural, religious and emotional phenomenom. Most I would suggest would shy away from dissecting or even viewing what is beneath the skin. They may even find it repugnant or distressing to look at.

Strangely the same individual will probably be able to view the meat counter in the supermarket or butchers shop with total equanimity. To look inside the body presents a much greater psychological challenge, to looking on the outside of it.

This is not a recent phenomenon. Indeed we probably are more familiar with our insides today than ever was the case. The reticence to look inside was to a large extent influenced by religious belief and the sanctity of the body as being the vessel for the immortal - and therefore divine - soul. These entrenched beliefs die hard.

One recent and welcome development in the west at least, is that those physically disabled are being treated with greater courtesy and consideration by those not so affected. The part sport has played in this transformation of public attitudes cannot be underestimated, but the disabled themselves would probably agree there is still some way to go before they are fully integrated and accepted by the rest of society. What is this other than the application of changing aesthetic values and judgements?

The Mediaeval Approach to Anatomy

Improving knowledge of the organs and their function slowly influenced medical and surgical practice. For example 'blood letting', based on the underlying Greek idea of 'humours', remained a therapeutic procedure right up to the end of the 19th Century, despite the fact it undoubtedly did more harm than good.

Strangely of course it is still practised but for a completely different reason, either in transfusion or to provide blood for others. Leaches are apparently coming back into fashion!

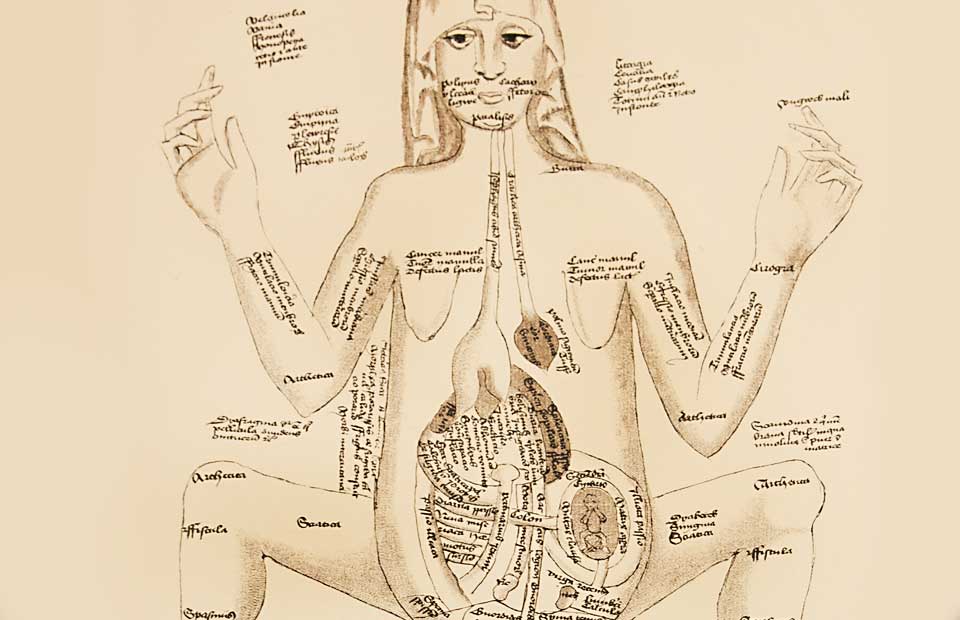

The following picture demonstrates the primitive way in which our medieval ancestors understood and represented human anatomy.

https://outlook.wustl.edu/archive-assets/img/story/slideshow/e_2.jpg

The mechanistic approach to the body, which later developed into a 'scientific' one, also displaced the beliefs that had dominated since Greek and Roman times through the writing of such individuals as

Hippocrates of Cos ( c. 460 – c. 370 BC), Aristotle (c. 384 - c. 322) and Galen of Pergamon (129 AD – c. 200/ c. 216) to name but three - ideas that remained amazingly resistant to change over nearly two millenia!

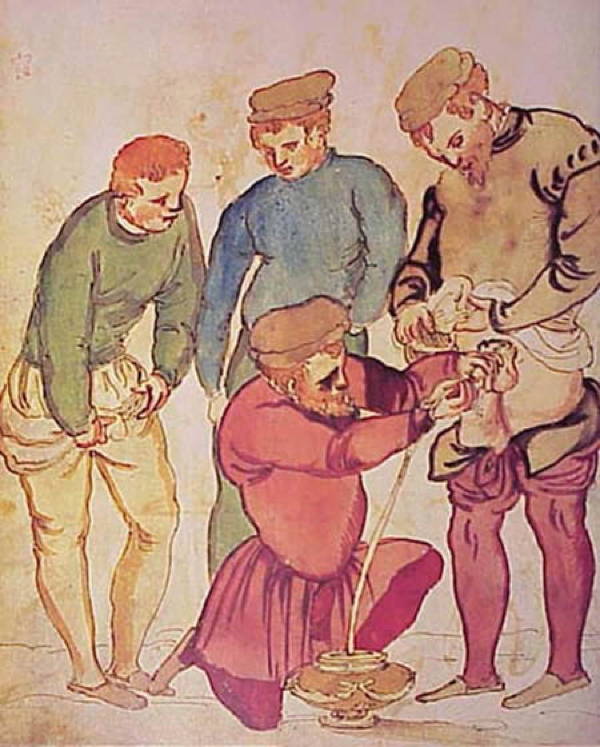

Note in the following image the professor remains aloof and does not get his 'hands dirty'. Students must have become familiar with the sight of the organs, but it was interpreted in the context of an ancient and inaccurate explanation of organs and their function.

For example prior to Harvey's discoveries regarding blood and its circulation via an arterial and venous system, the heart and blood was seen as a source of heat analogous to a furnace. The true purpose had to await discoveries in microscopy and chemistry to gradually unravel the true and elegant purpose and mechanism to supply oxygen and nutrients around the body and remove some of the by-products.

https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/564x/a5/55/f1/a555f1861e862ffe4a94d04b53e100cb.jpg

Much of the mediaeval understanding of the human body came from the results of warfare which for many was constant and brutal as was the treatment. Those that did not die from their wounds were likely to succumb to infection, the properties and causes of which were not understood until the Victorian era with the discoveries of Pasteur, Snow, Lister, Koch, Semmelweis and others and not effectively controllable until Fleming discovered 'anti-biotics' in modern times.(1)

Mediaeval Trauma Surgery

http://maggietron.com/medievalmedicine/images/possible_injuries.gif

Mediaeval Surgery

http://l7.alamy.com/zooms/8c4735fa69eb4c3fbafaa3f1692b2ed6/a-german-surgeon-in-the-16th-century-b86w5r.jpg

Ouch!

http://all-that-is-interesting.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/metallic-catheter.jpg

Good and bad 'humours'

It was a system that observed four apparent features of the physical world - earth, water, air and fire - which were projected onto their respective temperaments - 'melancholic', 'phlegmatic', 'sanguine' and 'choleric'. Of course the terms are still in use to this day but not in the same way.

The observed symptoms of disease were classified into an analogous four-part system of blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm, from which all diagnosis and treatment flowed, no doubt liberally intertwined with superstition, religion, alchemy, astrology and herbal concoctions, not all of which were un-efficacious.

Both the representation and understanding of the function of organs remained rudimentary until anatomical accuracy arrived with people such as the remarkable Leonardo da Vinci and more specifically Vesalius (below).

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

As a result not until what we regard as the Renaissance, do prevailing ideas change, and in centres of learning particularly in Italy and later in northern Europe, does scientific examination take place, in large part energised by the demands of art to be able to portray beauty based on anatomical accuracy.

Of course all the great artists were notable for this and in particular Leonardo da Vinci, who carried out and reproduced his own dissections. Also significant was the revolutionary work of Vesalius who not only produced amazingly accurate representations of the largely unseen interior, but published them with the aid of the newly invented printing press, so they could be disseminated - at least to the wealthy and centres of learning.

Just one example of Leonardo's anatomical work.

Sketches of a fetus in the womb, made between 1510 and 1513.

Credit: The Royal Collection (c) 2012, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

http://www.livescience.com/images/i/000/026/962/original/fetus-120508.jpg?interpolation=lanczos-none&fit=inside%7C660:*

Anatomical Accuracy

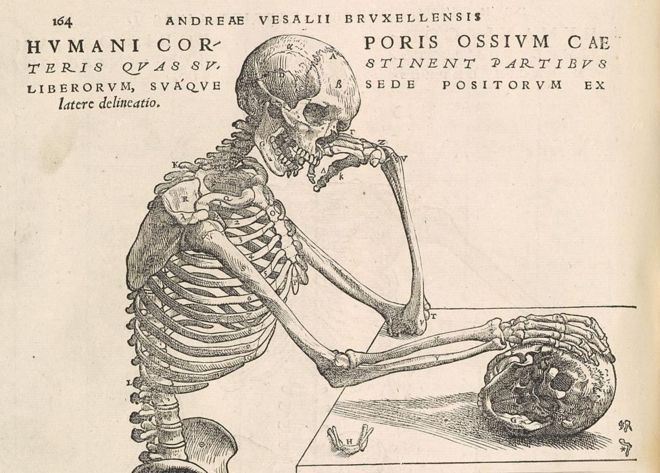

Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564)

http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/hommedia.ashx?id=10136&size=Small

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/660/media/images/78960000/jpg/_78960659_976newapr-n-00001-00002-a-000-00031.jpg

From: De humani corporis fabrica libri septem ("On the fabric of the human body in seven books") written by Andreas Vesalius published in 1543. It represented a major advance in anatomy.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b2/Vesalius_Fabrica_p372.jpg

We should not underestimate how difficult this advance was. The desecration of human bodies was still prohibited except under strict conditions. So only executed (hanged) felons were allowed to be used for the purpose. It explains to some extent the typical bodily positions they are shown in.

Not until the 17th and 18th Centuries did knowledge of anatomy and physiology really develop in parallel with scientific knowledge generally. Even in the 19th Century Edinburgh, a centre of surgical excellence, the difficulty of obtaining corpses for dissection could still lead to the scandal of Burke and Hare!

https://thechirurgeonsapprentice.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/1003.jpg

A 'Mechanistic' View of Health and Disease.

A 'mechanistic' view of health and disease, started to appear as an idea from the 17th Century onwards. It complimented a mechanistic view of the universe itself by thinkers such as Rene Descartes in France. It was the beginning of a scientific study of man and all aspects of the universe of which he was a part.

Descartes resolution between the spiritual and the physical was he postulated, the pineal gland located at the base of the brain where the two world connected body and soul. Strangely in our modern physiological understanding the pineal gland still has a pivotal role, and is still referred to as the "third eye". (See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pineal_gland)

René Descartes, L’homme…

http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/treasures/files/2011/12/QP29_D44_1729_fig_32_33_big.jpg

"René Descartes, L’homme…. “…I desire you to consider, I say, that these functions imitate those of a real man as perfectly as possible and that they follow naturally in this machine entirely from the disposition of the organs-no more nor less than do the movements of a clock or other automaton, from the arrangement of its counterweights and wheels.”"

John Locke (1632 - 1704)

John Locke was an early 'natural philosopher' and member of the Royal Society who was greatly influenced by Descartes writings and approach to intellectual reasoning.

From an early age he took a layman's interest in health and healing that he pursued during his scholastic career and were to prove the serendipitous cause of his social and political advancement. He liked to dabble in medical matters, regarding himself as a semi-professional physician, offering advice and intervention to those that sought it.

One of these was the very influential Antony Ashley Cooper, First Earl of Shaftesbury, who suffered from a very nasty suppurating liver cyst or abscess. Hydatid cysts result from a parasite infection in the cycle of a tapeworm carried by dogs and other animals. Infection is from contaminated soil, food or water.

Cooper was impressed with Locke's intellect and conversational skills when they met and adopted him as his physician, private secretary and confidant, which later embroiled Locke, whether justified or not, in deep trouble.

"Locke a Fellow at Christchurch, Oxford also worked with Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, among others. Richard Lower (1631–91), who performed the first successful blood transfusion, persuaded Locke to study medicine, and Locke attended the lectures delivered by Thomas Willis (1621–75) in Oxford sometime in 1664/1665. Locke's notebooks reflect the lecture and the experiments of the age.

"He became an assistant to an Oxford physician, Dr David Thomas and that year met a rising politician, Lord Ashley (later Lord Shaftesbury), who was greatly impressed with Locke's medical knowledge and they became friends. After being rebuffed he finally received his BM degree on 6 February 1675 after having fulfilled the academic conditions."

His letters and journals show that he was often consulted on a variety of medical subjects, seeing patients of both sexes and all ages.

Sometime in 1667 John Locke met Thomas Sydenham and embraced his medical ideas. Both held the other in high regard and Locke helped Sydenham with writing his works. Sydenham described Locke as having “few equals and no superiors”. Locke in turn described Sydenham as “that Great Genius of Physick”. In 1669 Sydenham and Locke collaborated in writing De Arte Medica, but this was never completed."

See: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2083071/

As an aside we may note that Thomas Sydenham (1624 - 1689) was later referred to as the "English Hippocrates", so praise for Locke from that quarter was no mean thing. A Sydenham quote I like, and which should perhaps be more applied today is, "I have consulted my patients' safety and my own reputation most effectually by doing nothing at all."

However what we might regard as Locke's 'big breakthrough' was his treatment in 1668, of what is likely to have been Lord Ashley's fatal liver complaint. After discussing the serious condition with Oxford colleagues, he had made and inserted a silver tube through the skin with such precision, that it drained the offending area without causing a peritonitis or requiring further invasive surgery, both of which would probably have been terminal.

Not for another seven years did he obtain a medical degree despite opposition as he had not been an undergraduate in the subject. The influence and intervention of Cooper, by this time Earl Shaftesbury and Lord Chancellor, fixed it for him though, and he was awarded his Bachelor of Medicine (BM) in 1675.

Even so he never practised as a full time physician, being involved in much more weighty matters of state although he retained his interest and advised friends periodically when requested to do so.

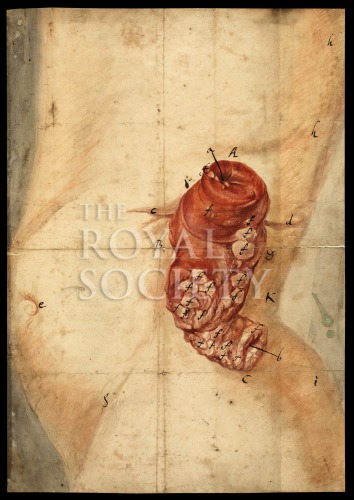

Abraham Vater (1684 – 1751)

An individual that over-laps with Locke and worthy of mention is Abraham Vater, son of a doctor and pioneer of descriptive surgery at Leipzig and Wittenberg universities. (Of course there is no personal reason for doing so!)

The author of hundreds of academic papers describing both anatomical details and surgical procedures - before anaesthesia of course - he marks a sea change in both knowledge and technique that rapidly spread across the main centres of Europe.

For his work and reputation he was very unusually recognised when he visited Britain in 1722 by being elected to the Royal Society.

Vater's reputation and achievements are little recognised today, however he leaves his mark on every human alive, as silent witness to his beneficial impact. The "Vater-Pacini corpuscles" surrounding nerve tissue and the "Ampula of Vater" where the pancreatic duct joins the duodenum in the small (but very indispensable!) small intestines, are named after him!

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Abraham-Vater.jpg/220px-Abraham-Vater.jpg

Study of an exposed human colon and small intestine

Date

1720

Description

Large study of the human torso with the colon and intestine exposed. From a manuscript copy account “Historia intestini coli transversim secti et a vulnere propendentis per Abraham Vater M.D.” [“History of the small intestine and colon...”] in which the anatomist Abraham Vater of Wittenberg describes in a letter of 1 October 1720 to the Royal Society, the consequences of a wound inflicted upon George Deppe at the Battle of Ramillies in 1706. Deppe subsequently lived with a severe prolapsed colostomy, illustrated here. Not signed.

https://pictures.royalsociety.org/image-rs-9823

The development of modern ideas of medicine and treatment

The necessity for a divine or spiritual dimension, that had dominated human thought since the beginning of recorded time, was progressively and slowly eased out by a more 'scientific' one, based on actual observation and discovery.

Philosophical reasoning took on an 'empirical approach' that demanded that only that which could proved with the senses should be believed.

This was a process that led from deism to atheism, via arguably agnosticism, and from superstitious or divine revelation, to a 'scientific' approach - a term first used as late 1834, proving how relatively recent the whole approach is in the scheme of things.

The scientific method was essentially practical and 'hands-on' approach, playing with materials and substances: observing, theorising and testing by controlled experimentation, leading to discovery and proof. Across a whole range of subjects, it led to the replacement of old ideas with better more accurate ones, and to their practical application in medicine and surgery.

Medicine became a 'science' that emerged in the 19th Century, along with the many others that we recognise today - now studied at universities across the world.

First Painless Surgery Utilising Ether

http://cookit.e2bn.org/library/1244058113/760pxsouthworth_26_hawes__first_etherized_operation_28reenactment29.original.jpg

Humphrey Davy, (1778 - 1829) an early example of the new breed of experimenters, who in popular culture is remembered principally for invention of the Miners Safety Lamp, which for the first time allowed artificial light underground, without an accompanying risk of explosion, is probably the least of his achievements.

From his early training in a humble Apothecary's shop in Penzance, he became fascinated by the chemical substances with which he was dealing, and before he was 21 had discovered Nitrous Oxide and it amusing effects on people when inhaled and thus given the name of "laughing gas". It provided the germ of the idea that gases could have beneficial medical applications.

By 1807/8, by now working in Bristol, a thriving port city, he had isolated potassium, sodium, calcium, strontium, barium, magnesium and boron, thus effectively founding the modern understanding of Chemistry, the elements of which were to be later codified by Dmitri Mendeleev (1834 - 1907) into what was called 'the Periodic Table', on which all future understanding rested, leading to the Nuclear Age.

But that boy Davy and his inquisitiveness can be seen to be a factor via his protegee Michael Faraday, (1791 - 1867) thirteen years his junior, in the whole unravelling of electro/magnetic energy on which the world now depends.

Their discoveries regarding the effect of gases and electricity on human bodies, that created much amusement and entertainment initially, also had practical applications also in the medical and surgical sphere, specifically in anaesthesia, diagnosis and treatment.

The nineteenth century was thus a major tipping point in man's understanding of himself and his world, in which old metaphysical ideas were no match for the new more accurate ones, on the anvil of discovery.

The religion versus science debate, that still remains current, came to a head in 1860 when Thomas Huxley (1825 - 1895) "Darwin's Bulldog" and "the premier advocate of science in the nineteenth century for the whole English-speaking world"., and Samuel Wilberforce, (1805 - 1873) Bishop of Oxford came head-to-head on the subject. From it can be dated the preeminence of the scientific approach and the decline of the Christian religion.

Supernatural belief systems may still remain important in the lives of most humans on the earth, but it it is of a quite different quality, that existed prior to the 18th Century. Then for most humans on the earth, the metaphysical was also fact.

It can be argued that Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 - 1900) put the final philosophical nail in its coffin and Julius Robert Oppenheimer (1904 - 1967) - who famously said on witnessing the first atomic bomb "I am become death, the destroyer of worlds" effectively the power of the Creator, demonstrated in modern times what this new-found God-like power could produce. He is also quoted as saying: "The optimist thinks this is the best of all possible worlds. The pessimist fears it is true."

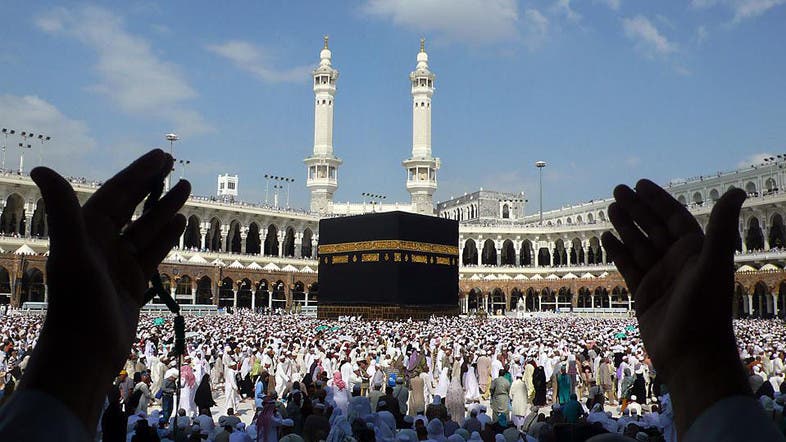

Modern 'Clash of Cultures'

https://vid.alarabiya.net/images/2013/10/03/71809526-d77b-4a51-9213-1020b95ee5d1/71809526-d77b-4a51-9213-1020b95ee5d1_16x9_788x442.jpg

The so-called "clash of cultures", much manipulated by political power brokers today may be seen as the continuing evolution of the issue. There are those that believe that the constant improvement of man and promise of an essentially godless scientific method, have a very pessimistic side; others that only science offers hope for the future of mankind and the global environment. Is the essence of the issue one of atheistic hedonism v. theistic asceticism?

The influence of the religions in the way people think about themselves and their world may conflict with a scientific one. Whether faith and religious belief can be reconciled with factual knowledge about the way in which human and global systems work is a debate that will continue. It would appear that religious belief is now in the God of the Black Hole or of the human imagination, or is it just a mechanism by the power brokers, to control the masses?

https://3a09223b3cd53870eeaa-7f75e5eb51943043279413a54aaa858a.ssl.cf3.rackcdn.com//world_04_temp-1364820495-5159820f-620x348.jpg

An evolving health philosophy

Of course if there is no need for a God, there is no need for a 'soul' and despite every effort, none has been located. Yet it is hard to believe that we are not, in some indiscernible way, more than the sum of our observable parts, however remarkable and sophisticated we find them to be. There are always deeper strata to explore, more intricate systems to discover, as with the current genome project and other discoveries that have provided insights into what it is to be 'human', as never before.

Some of these beliefs and practises are retained to various degrees around the world. In the 'enlightened' west we still cling to the notion of a 'magic bullet' and miraculous medicine, within the context of a mountain of pills and interventions, that may not be so far removed from what is described above.

A big difference however is an accurate knowledge and description of the purpose and function of bodily organs and processes in microscopic and chemical detail unavailable to earlier generations and civilisations. The "germ" and other theories transformed notions of disease causation and transfer, that with other environmental advances particularly in the area of sanitation and water supply, has changed the landscape of disease but not eradicated it as current vital statistics and heath industry prove.

Whether we are healthier now than previously, has to be qualified by age, occupation, wealth, personality, habits, nationality and location. Similarly the chances of getting certain diseases or surviving them. In all this medical intervention may play a part but it is not always decisive in either cause or cure. Although modern medicine has high status, its effectiveness may be over stated.

There are still many diseases and conditions for which it can provide little or no help. Indeed despite the enormous advances in some parts of the world, the scientific approach, invention and liberated behaviour of populations, has undoubtedly contributed to the pattern of poverty, starvation and disease that we witness in the world today. The progress of past ages still has a long way to go if humans and our organic world are to survive.

However, the more people are aware how their bodies work, the more likely it is hopefully that their behaviours will be kind and intelligent to it and others, although the experience of professions alligned to medicine may support the opposite premise!

REFERENCES (1)

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (1818 - 1865) was a Hungarian physician of ethnic-German ancestry, now known ...Semmelweis proposed the practice of washing hands with chlorinated lime solutions in 1847 while working in Vienna General Hospital.

Louis Pasteur (1822 - 1895) was a French biologist, microbiologist and chemist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization.

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, OM PC PRS (1827 – 1912), was a British surgeon and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery.He promoted the idea of sterile portable ports while working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. Lister successfully introduced carbolic acid (now known as phenol) to sterilise surgical instruments and to clean wounds.

Robert Koch (1843 - 1910) The German doctor Robert Koch is considered the founder of modern bacteriology. His discoveries made a significant contribution to the development of the first 'magic bullet' - chemicals developed to attack specific bacteria. Koch was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1905.

Sir Alexander Fleming, (1881 - 1955) Scottish bacteriologist best known for his discovery of penicillin.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.